In July, a fireball soared across the skies of the Central Desert, and dropped a meteorite deep in the WA outback. In November, Dale Giancono, Iona Clemente and Michael Frazer headed east and recovered the rock.

By: Michael Frazer

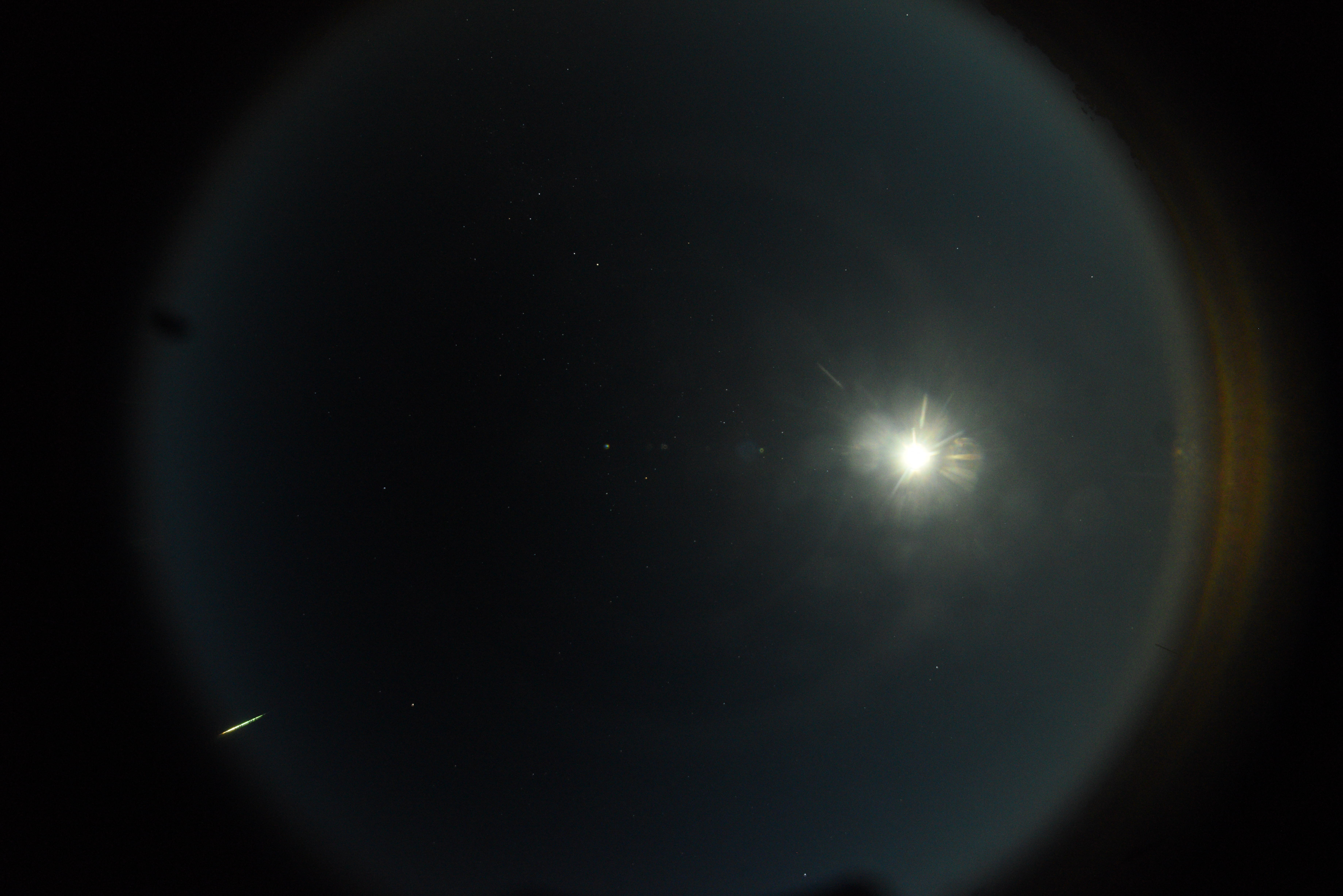

The Fireball

In July this year, the DFN and Curtin University hosted the Meteoroids conference in Perth. While the conference was a big success, we didn’t quite have room in the budget for a fireworks show – luckily, the universe came through. Just after 9 pm local time on the final night, a fireball soared across the skies of central WA, and dropped a meteorite deep in the WA outback, about 400 km NE of Kalgoorlie.

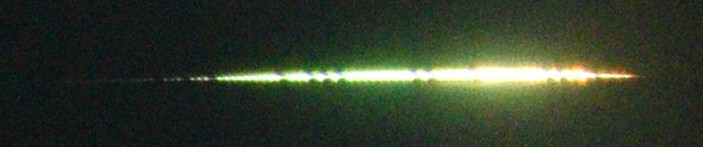

Our first processing of the fireball imagery suggested a small final mass – around 50 g, a centimetre or two across. The fall site was also in thicker bush than the clean, empty plains of the Nullarbor, where we prefer to search. Given the small final mass and unfriendly terrain, we decided it probably wasn’t worth a full search.

But this was also the first meteorite dropping fireball that Dale’s camera prototype observed. So this fireball was a good candidate for doing the detailed analysis that the reviewer was asking for. Denis Vida (Western University) ran a detailed fragmentation model and found an estimated final mass of around 600 g, possibly more – much bigger than initially thought. With prospects of a larger mass, we asked our Slovak friends to take a look at the spectrum. Matlovič Pavol and Veronika Pazderová: “the spectrum is a bit odd and there are some hints it could atypical, but it’s hard to confirm”.

A buzz went around the DFN office. Was the composition interesting? What was causing the difference between our models? And, importantly, maybe there is a big piece lying in the bush somewhere… There was only one way to find out.

Dale was excited about closing the loop on his fireball. Hadrien about the spectrum, and also his bet a year ago with Veronika that we would find a spectrally recorded meteorite before she finishes her PhD.

Day 1

Up early, we jump into our field truck, Rhonda, and hit the road out of Perth. Breakfast is at the legendary Baker’s Hill Pie Shop, and morale is high. We pass through Kalgoorlie later in the afternoon, where we make the only bad decision of our trip – not buying beers. We’d come to regret that. We leave Kal by 4 pm and head east for another couple of hours, leaving civilisation behind, and eventually set up the swags for our first night in the bush. Dinner is pesto pasta beneath the glow of the stars and waxing crescent moon. Maybe we’ll spot another fireball, if we can just stay awake…

Day 2

We head out beyond Kalgoorlie on smaller and smaller roads – turning off the highway onto an unmarked bitumen road, from that onto a wide dirt road, then a narrow dirt road. By the time we stop for lunch (and 25 mandatory squats to keep the legs active), we’re on a bush track that winds its way around sand dunes and between trees.

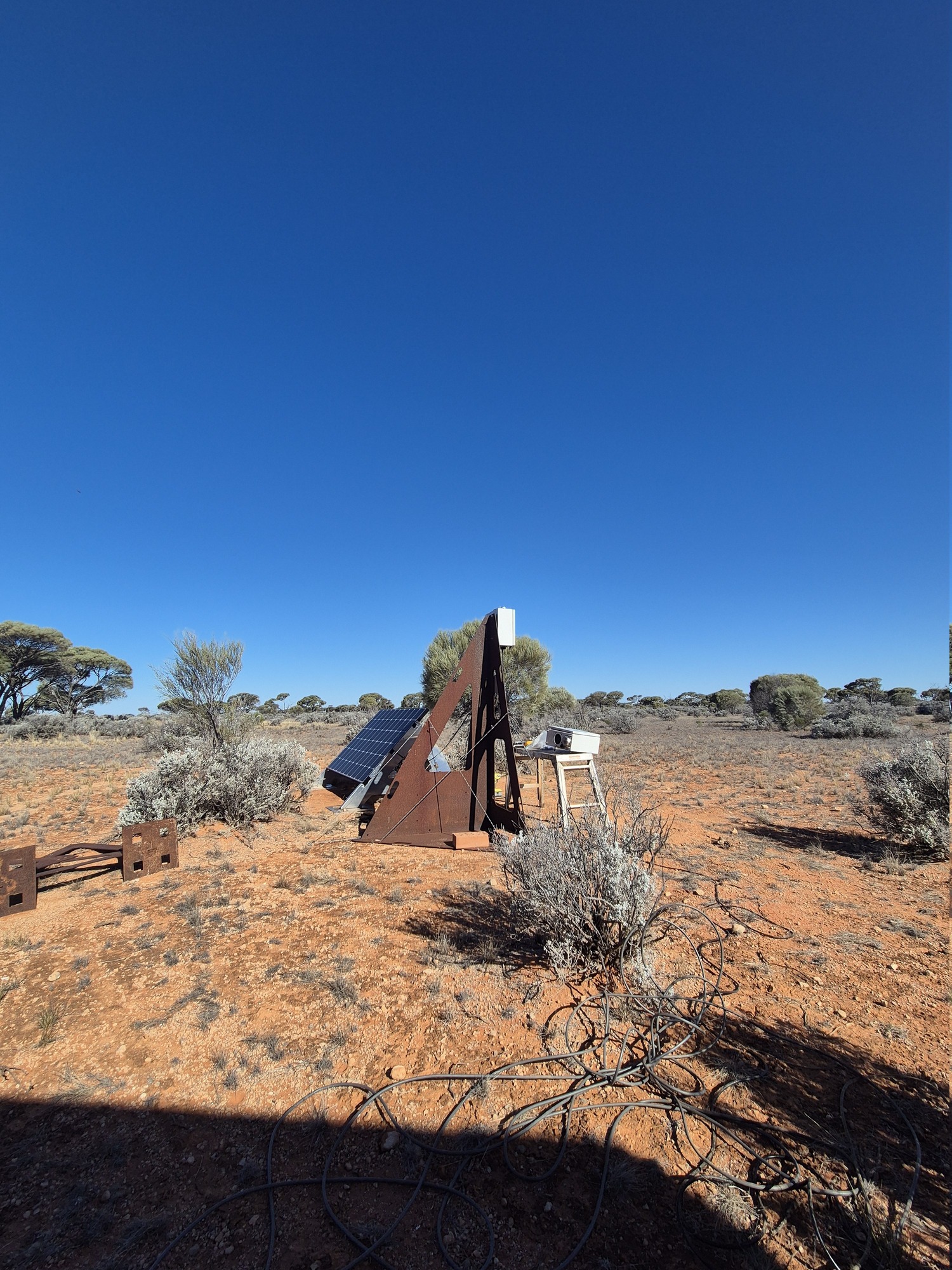

By about 2pm, we make it to our first destination – the closest DFN observatory to the fireball, so remote that it’s an offline system, meaning that we can’t communicate with it from our base in Perth and it saves all data locally. Last service was over a year ago by Iona, Veronika and Hadrien. We have two jobs here – service the camera (swap the old hard drives out for new ones, replace the DSLR body, and check the solar panel and battery system), and check if there’s any useful data that could help narrow the search zone for our meteorite. Unfortunately, the local caretaker of the camera system (a tiger moth caterpillar) had been slacking off recently, so we have to spend a bit longer servicing that we’d like. Once we do get our hands on the data, we find that the local weather on the night of the fireball was cloudy, so the camera didn’t have any useful observations for us. Oh well! We set it the observatory running, bid the caterpillar farewell, and hit the road again. See you in a year, camera.

We continue on towards the fall site, and peel off the track once we find a spot that looked like a good place to set up camp. Dinner is a Thai yellow curry, cooked mostly without a head torch in an effort to keep the moths out of the saucepan.

Day 3

Up at dawn, we hit the road early hoping to arrive at the fall site by mid-morning, where we can set up camp and begin the first stages of the drone survey. We’ve been impressed at how nice the roads had been so far – comfy 4WD tracks, no major obstacles. So we’re surprised when, around 9:30 am and 15 kms from the fall site, the track before us vanishes into thick scrub and bush. Did it turn off to the north? The south? Maybe it’s just behind that group of trees, or beyond that patch of spinifex… When we check our satellite imagery, we can see the track that we’d just come along from the west, and where the track continues to the east – but with a 500 m gap between the two.

So, starting on one side of the 500 m-wide chasm, we put our faith in Rhonda and bravely push forward into the wilderness… only to quickly hear the hissing of one punctured tyre, and then a second, sliced by the sharp roots of two of the many dead bushes in the area. We spend a few hours swapping the tyres for the spares in the back and scouting ahead on foot, clearing a path with a shovel and pick so that we can make it through the remaining 300 m. We eventually make it to the fall site, and set up our home for the next few days.

Day 4

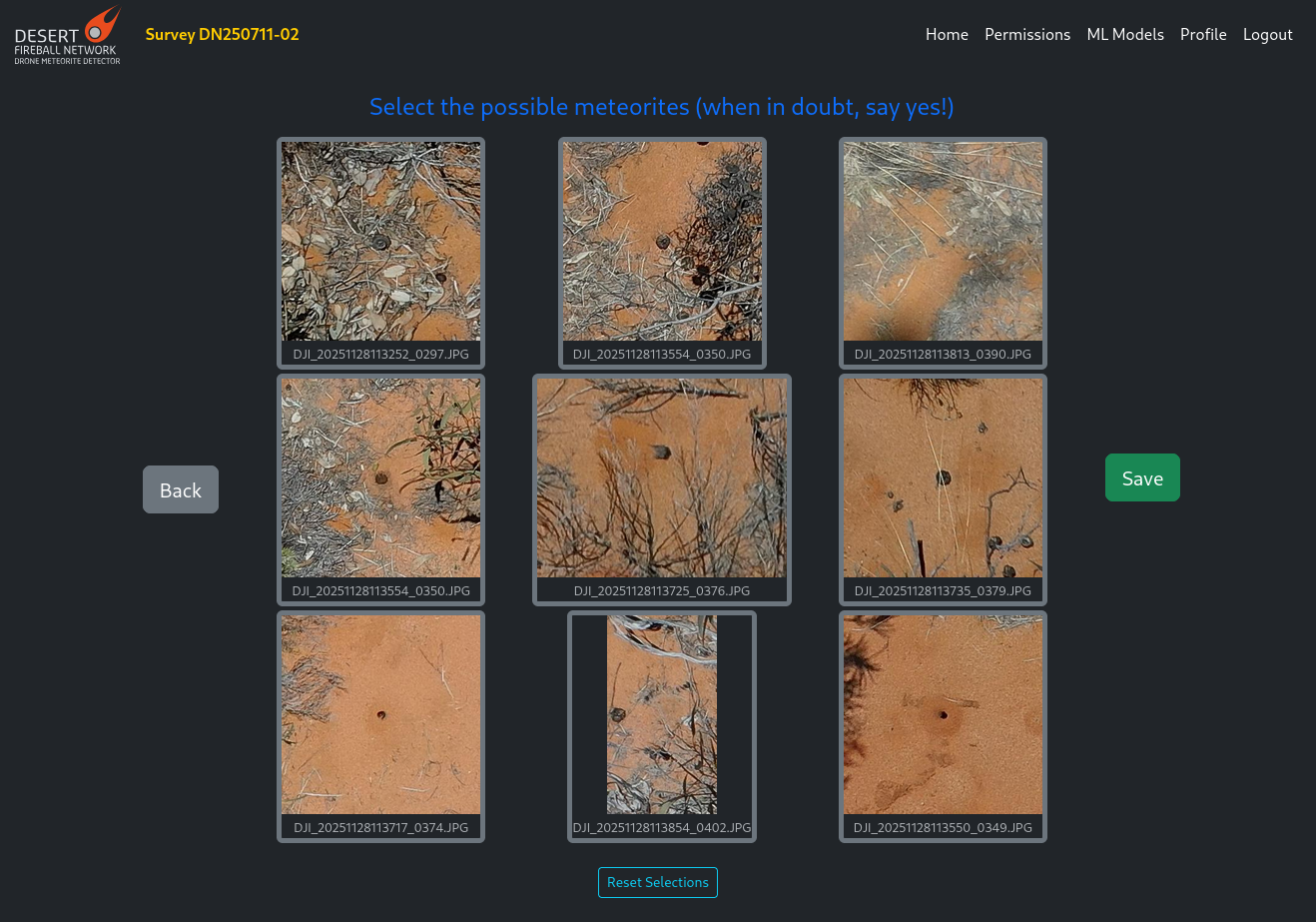

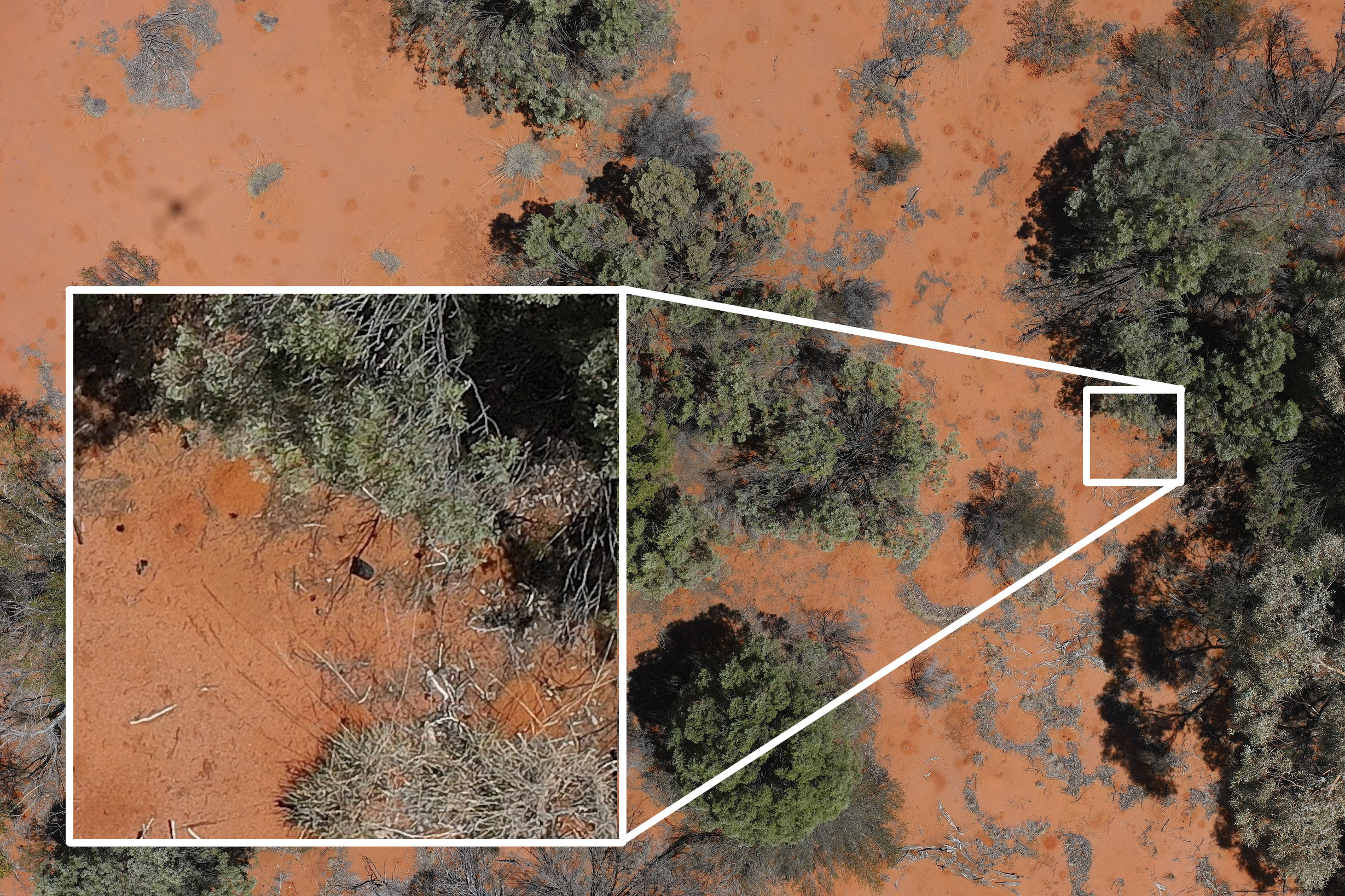

Before sending the drone out to find the meteorite, we have to teach it what to look for. Iona and Michael head out with a bag of 20 ‘meteor-wrongs’ (terrestrial rocks spray painted black) and lay them out within a few hundreds metres of camp, while Dale flies the drone overhead. This helps the machine learning model identify small, black objects within the context of the local environment, like the colour of the dirt (red) and types of vegetation. By the time we’ve finished the training survey, the sun is getting higher in the sky and the temperature is starting to climb with it.

We begin the main survey around 11 am (35° C). We hide in the shade, sipping on juice boxes, but by noon the drone – exposed to the full brunt of the sun – is starting to complain of overheating. We try cooling the batteries by putting them in the fridge and cranking it to maximum (ironically powered by the solar panels on the roof), but we’re only delaying the inevitable. By about 1 pm (39° C), the drone is grounded, so we start processing the data that it has collected.

Our full search area is 3 km by 0.5 km. By this point, the drone has been able to survey about 15% of that, and has detected about 5,000 Stage 1 candidates – small black surface features, mostly gumnuts, spider holes, and kangaroo poo. Over the next hour or two, we (with the help of the team at Curtin) sort them into ‘could be a meteorite’ and ‘definitely not a meteorite’ groups. The ‘could be a meteorite’ candidates are passed to Stage 2 for a closer inspection, and if we like the look of them, we pass them to Stage 4 to be checked in the field. We used to include Stage 3, which was a drone follow up image, but found that this was often less efficient than just going straight to Stage 4. By the time the temperature starts to creep downwards, we’ve collected about 50 Stage 4 candidates, and the shadows are too long to continue the drone survey. We go for a wander to check them out… and find 50 gumnuts.

By 8 pm, dinner (satay stir fry) is finished and the sun has set, but the heat and still air remain. Sitting in silence around an un-lit campfire, we hear a strange noise from the south – a faint whoosing that grows louder over about 20 seconds, until the trees on the far side of camp bend over and a wave of cold wind crashes over us. A gale kicks up so we tie down camp, and half an hour later, the temperature has dropped by 20°. We head to bed tucked beneath our sleeping bags. Life in the desert.

Day 5

With cooler temperatures forecast, we get cracking on the drone survey as soon as the sun is high enough to prevent long shadows. Dale and the drone work in perfect harmony and, with Iona, Michael and the Curtin team processing Stage 1 and 2, we have a steady stream of Stage 4 candidates coming in by mid-morning. We pull fly nets over our heads, press play on the music, and head out into the field. From then until sunset around 6:30 pm, we sort another 20,000 Stage 1 candidates, and check about 400 in the field. Lots more gumnuts, but no meteorite yet…

That night, we were visited by a pair of camels who came to check out our camp (probably lured by the smell of the Mexican chilli we had for dinner). We’re still not sure who was more spooked – us or them!

Day 6

Our final day in the field begins with “crêpes” (rye bread wraps) toasted in butter and filled with melted chocolate, peanut butter and sliced bananas. While we’d lost time on Day 3 with the puncture and Day 4 with the weather, we’d made great progress on Day 5 and had managed to cover about half of the survey area. If we could keep the pace up for Day 6, we’d have a good chance of covering the full area and maybe finding the meteorite! As we’re preparing to head out a bit after 6 am, we realise that the data that we were transferring overnight has crashed the website that we use for completing the survey in the field. We give Hadrien a call back at base, thinking we might be stuck for a few hours, but he and Lewis (who helped develop and maintain the online platform) are able to get it sorted quickly despite the early hour. Thanks Lewis!

By the time we return to camp for lunch on Day 6, we know the ball game. The drone survey is done, and all 31,153 Stage 1 candidates have been sorted, giving us 728 Stage 4 candidates to check in the field. We’d knocked over about 400 in the first day, and another 130 before lunch, so we have 200 left. We just have to hope that the meteorite is one of those 200, and hasn’t fallen into a bush and been missed by the drone, or fallen outside of our calculated search area.

By 5 pm, the sun is getting closer to the horizon, and we’ve spent another few hours looking at 140 gumnuts. 60 candidates left. We’re still hopeful, but the numbers are starting to stack against us. We divide the last 60 into 20 each, and set our for our final sorties of the trip. Michael finishes his first and radioes in – “Ah well, no space rock this time. Heading back to camp.” Iona’s call comes next – “Yep, all done too. See you at camp.” Then Dale’s.

“Guys… I found the fricking rock!”

Radio silence.

“Dale, c’mon, this is no time to be playing jokes on us.”

“Guys, I’m serious! This is the most meteorite-y looking meteorite I’ve ever seen!”

Ten minutes later, the three of us are crouching on the ground around candidate number 727/728. The meteorite we’ve been hunting for.

That night, we pull down camp, and three days later, the DFN’s 11th successfully retrieved meteorite with a known orbit (3rd using Seamus’ drone methodology) is in the lab back at Curtin.

Acknowledgements

The find.gfo.rocks drone searching platform has been developed thanks to the support from Astronomy Australia Limited’s ADACS program program, with lead developer Lewis Lakerink (Swinburne University), and managed by Hadrien Devillepoix on the Curtin side. This fantastic new capability builds upon Seamus Anderson’s PhD work at Curtin University. On the infrastructure side, the system relies on the ARDC Nectar research cloud for computing, and the Pawsey Supercomputing Centre’s Acacia object store for data storage.