Mia recently joined the planetary science team at Curtin Uni. After years working with radio astronomers and their spider-looking antennas, she embarks on a mission to hunt for space rocks!

day 0 - packing

Captain’s log, star-date 20231201. I am about to embark on a voyage with my new crew. Our mission: to study an ancient landscape using aerial methodologies developed by science officer Anderson, with the goal to recover a meteorite that we observed to fall in this remote location. The day was spent in preparation for the long journey ahead. Our chief engineer, Giancono, repaired power inverters onboard our vessel, SSTC Rhonda, at which point we began loading supplies. It can be observed that the cargo tray is at full capacity, leaving no room for luxuries. Thankfully we managed to include 7 necessary different cheeses, and Anderson is confident in finding room for post-dinner beverages. My crewmembers enjoy a diet that I am not wholly familiar with, but have decided to embrace for the next 9 days, called ‘vegetarianism.’ I look forward to sampling many alien-looking delicacies from the camp stove in the coming nights.

We will be sleeping under the stars, a fact which I am much more comfortable with now that I have prepared some arachnid-repellant. I have been gifted with a uniform patch, as a symbol of this mission. I am deeply honoured and will wear it with pride, once I figure out how to attach it to my person. Our journey begins on the morrow at 0800, and conditions look promising. I will attempt to provide a daily status update, comms permitting. Walker out.

day 1 - driving

Captain’s log, star-date 20231202. I said my farewells to the feline beasts I keep at home. They did not care. An abundance of space was declared in SSTC Rhonda’s rear compartment, which would serve as the Captain’s chair for the first leg of our journey. We stopped at a well-known eatery and were notified by a fellow captain that Rhonda was losing precious cargo from the side canvas (cans of Asahi). We quickly rectified the situation and checked over the rest of our craft. Giancono assured me that a leak found on the underbelly was simply waste water from Rhonda’s life support/air refrigerant system, which worked overtime on the 38C day. I decided to calculate if we had sufficient water of our own for the trip, using esteemed adventurer Russel Coight’s estimation of “three litres per day, per person, per man, per degree over 25 degrees celcius, per kilometre if walking on foot, in the winter months dividing it by two, plus… another litre… at the end.” 3x9x3x2x10x3+1 =4861L

..We continued on, while I double-checked my maths. SSTC Rhonda traversed ten degrees of the planet’s longitude (approximately 1000km) over the course of the day. At approximately 1800, as the local star (Sol) neared the horizon, we decided to make camp. A large welcome party of the local populace (flies) greeted us, and were incredibly friendly well into the evening. I adjusted my sleeping quarters after initial setup, as they did not come equipped with an in-built deflection shield (fly netting). As a makeshift shield, I utilised some mesh with weighted edges that I had brought with me to protect open foodstuffs. The logic being that, to the insects of Earth, my human skin is an open foodstuff. By fortunate coincidence, it took exactly the same amount of time for me to finish configuring my bedroll, as it did for Anderson to declare dinner was ready. Without external comms, we passed the evening hours in much the same manner as we had all day (i.e., Anderson talking science), but this time accompanied with scotch, and a view of orbiting satellites and shooting stars. It was very pleasant. Walker out.

day 2 - observatory visit

Captain’s log, star-date 20231203. The days begin at star-rise (4am in this new time zone). We reached the predicted fall site of the meteorite late in the afternoon, after many more hours of travel, mostly off-road along a dingo-proof fence and dystopian train tracks. Giancono pushed Rhonda to warp speed to overtake a road train at one point. We sighted cattle and camels, and had to plot new course headings more than once to avoid kangaroos who were determined to get in our path.

Our crew was briefly commandeered to assist another science mission at Kybo. This was swiftly resolved, with Anderson’s expertise and years of training (the machine was turned off and on again).

We were hastened by weather conditions unfit for sustained activity (43C, high winds). Strong winds continued into the evening, and while this made putting up the gazebo difficult, we do not anticipate it will hinder our drone-searching efforts. Walker out.

day 3 - first day of meteorite searching

Captain’s log, star-date 20231204. The search for a fallen space-rock begins today in earnest.

We discovered that due to a map upload error, we have parked SSTC Rhonda on the end of the fall line, meaning that there is a non-zero chance that one of us has unwittingly slept on, stepped on, or even urinated on the meteorite since we arrived.

I received my remote pilot’s license approximately 4 years ago but have not flown since. To mitigate the risk of a rapid, uncontrolled descent (crash), I reacquainted myself with the controls using a small and relatively inexpensive-to-replace drone. I can report that no repairs have been necessary.

We covered 90% of the fall line in 12 flights, and performed our initial analysis on half the images (~6000).

In the evening, as the sun set behind a distant thunderstorm, we decided to go for a walk. Anderson, who is aiming for another meteorite detection with his drone method, gave us strict instructions “not to find the meteorite with our eyes”. When he waved us over to his location a few minutes later, I was ready to remind him of his own words - instead, he showed us his discovery of a cave, now known henceforth as ‘Anderson’s hole’, now added to Starfleet’s navigational repository. Walker out.

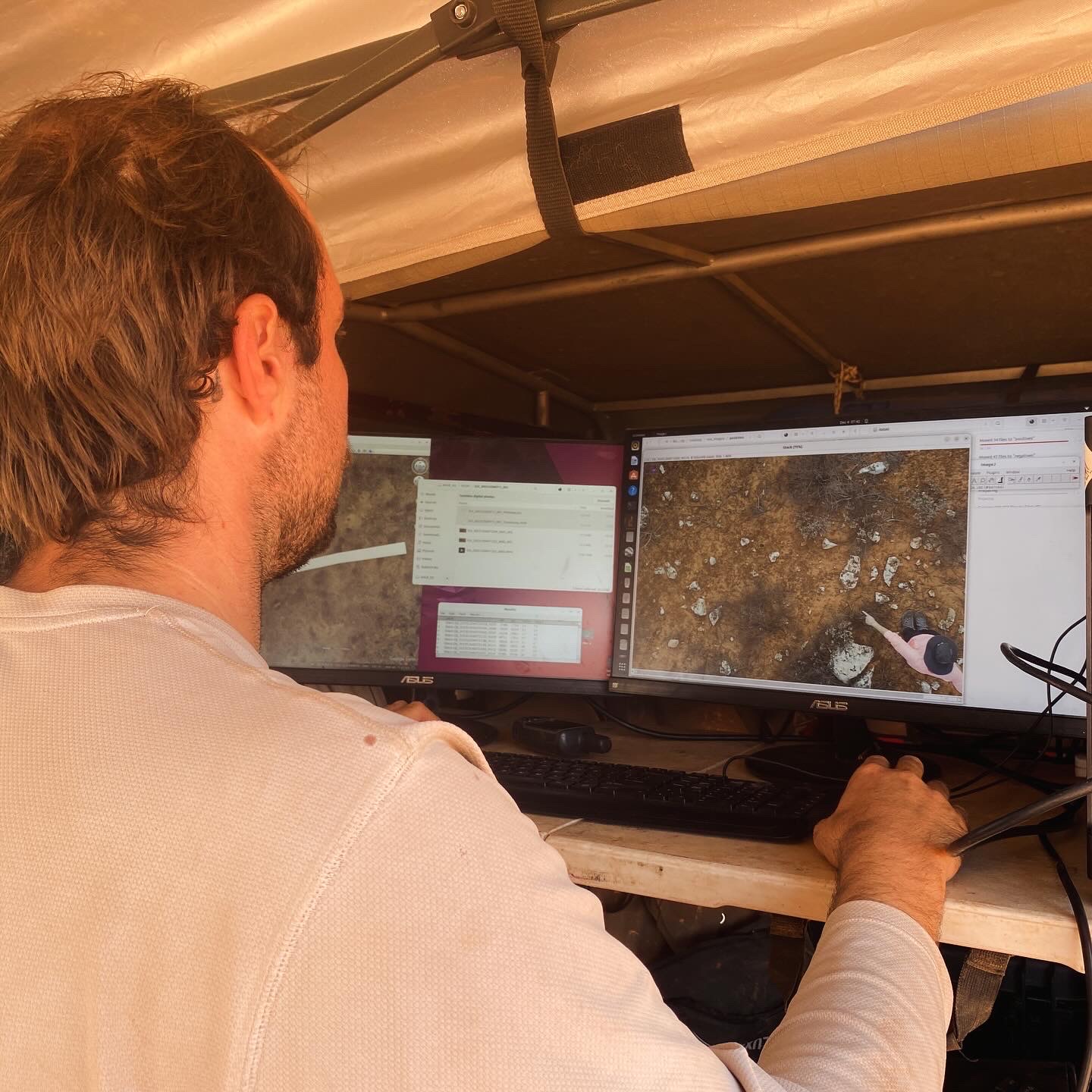

Supplemental log, on the Anderson method of meteorite hunting.

Instead of the traditional police-line search, we are using a large drone equipped with a camera, and software that has been trained to detect anomalies in an environment, to image our meteorite and determine its location. This is an incredibly complex process and I am still in awe that it is possible. Firstly, we take some training data in the local environment. To do this, we gather small meteorite-shaped rocks and spray-paint them black (which is how the actual meteorite is likely to appear), and take photos of them with the drone.

Then we program a flight path into the drone to take photos over the entire predicted site of the meteorite, or ‘fall line’.

The meteorite we are hoping to find is only expected to be 50 grams, or a couple of centimetres across, within a 5km-long, 500m wide rock-strewn field - rather like finding a needle in a haystack! Even with the drone flying at approx 10m/s, this stage can take more than a day to complete, after we factor in all the trips the drone needs to do with a limited battery.

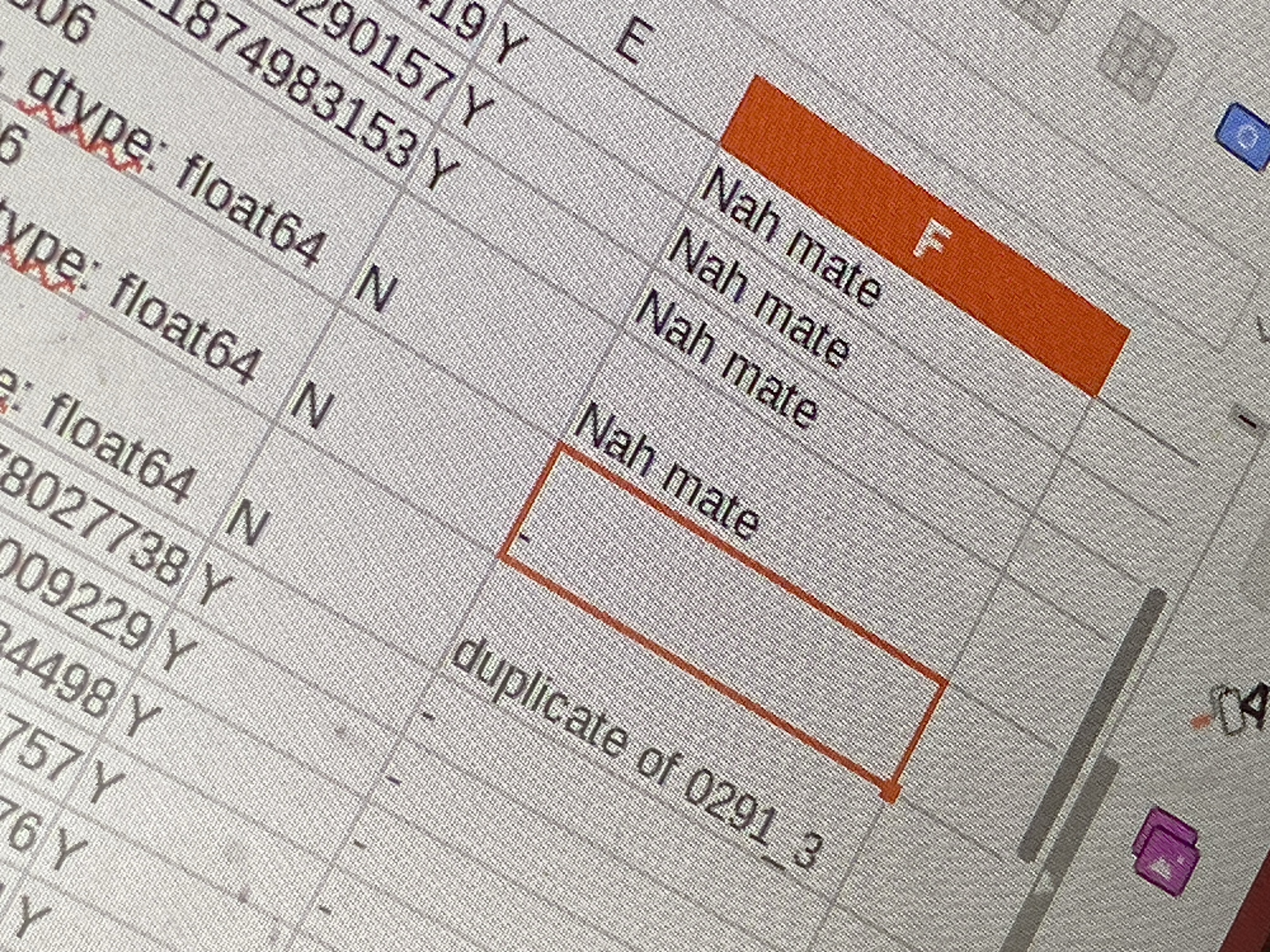

When all the drone data is copied to the computer, Anderson runs his code, which goes through the images and identifies meteorite candidates based on the training data. We then begin a four-stage identification process:

1) a first-pass look at everything the drone thinks could be a meteorite. We aim to cull about 90% of the possible candidates (from over ten thousand to a few hundred). Unfortunately, kangaroo poo looks a lot like a meteorite to the drone and the untrained eye!

2) we look again at the shortlisted candidates, this time with the rest of the image as context.

3) we send a small drone out to take a closer look and see if we can rule out any more.

4) finally, we plot a route and go out on foot to look at the suspect rocks. Once we think we’ve found the meteorite, we don’t want to touch it, because that might contaminate it. So we will use tongs to put it in a sample bag!

day 4 - the sledgehammer test

Captain’s log, star-date 20231205. Giancono required a drone assist to exit his sleeping quarters this morning.

We have processed the majority of early candidate images, and the day felt long. Likely moreso to Anderson, who had the additional task of supervising Giancono and myself while we got up to speed with his system, while dealing with multiple power outages (despite our ‘petroleduct’ for the generator). Anderson also suffered our inexpert feedback and even updated his code on the fly - truly admirable.

I did not realise how alike meteorites can appear to animal faeces when imaged from the drone, or know that state-of-the-art planetary science would involve dismissively saying ‘poo’ hundreds of times. Our shelter is beginning to fail in the high winds, but also due in part to the high frequency with which my head has connected to one of the supporting struts.

Giancono found a handful of (non-meteorite) rocks and enthusiastically used the sledgehammer to open them. The wash bucket was an unfortunate casualty of this process, but has been precision-repaired with the best tools known to man (gaffer tape).

Additional. There is high geomagnetic storm activity, and we are hopeful of spotting an aurora in the evenings. There is no light pollution out here, and even without additional spectacle the night skies in this vast landscape are wondrous. Walker out.

day 5 - the rock

Captain’s log, star-date 20231206. Today was fuelled with a sense of purpose and urgency, as we are already on the last packet of coffee and baby wipes. Rain hindered our efforts with the small drone, so I went analog and walked to all of the closest meteorite candidates using my trusty tricorder (GPS navigator app on my phone). Most of the candidates turned out to be poo, holes, or small bushes that appear very dark when imaged in the afternoon sun. We did pick up a handful of different black rocks, including one of our own training rocks that we’d left accidentally.

Giancono thought he found something, and as we walked to the site, Anderson reminded us that our team name is ’low expectations’ and that “getting excited is strictly forbidden.” Anderson takes all candidates seriously (even the ones that Giancono and I identify, as non-geologists), flattening himself to the ground to inspect the rock and learn its story.

The rock was not our rock. But neither was the next one Giancono picked up and pocketed, while on another mission to another drone-imaged candidate. Anderson, upon seeing the rock that was brought back, said verbatim: “Wait. F*ck the f*ck off.” He would ‘stake his PhD’ on this rock being a meteorite.

It is very small, only 1.4cm or 5-10g (as opposed to 50-70g), so it is probably not the one we are hunting, that fell approximately 6 weeks ago. The drone algorithm is expecting something larger, so it’s likely it was not even flagged as a candidate - the only way to tell for sure is to bring it back for analysis. The ‘Anderson conjecture’ is that we over-estimate the mass of our meteorites, generally speaking, however with such a conservative prediction in this case it’s likely our rock is still out there. In addition, our science team predicts there is approximately 1 meteorite per square km in the Nullarbor (due to the age of the surface), so we are continuing our mission as if we did not have such an eagle-eyed and providential crew member in our midst.

Giancono has been granted first shower privileges for his find, which will hopefully take off the bulk of the caked mud on his legs, which bares a disturbing resemblance to blood.

We completed more of our stage 4 analysis with the large drone, and then an already excellent day ended with one of the most beautiful sunsets I have witnessed in all my life. I am overwhelmed with gratitude that I can participate and share this experience. Walker out.

day 6 - the storm

Captain’s log, star-date 20231207. We made further adjustments to the drone system, in order to ‘enhance!’ the remaining images and rule out more of the final meteorite candidates. Coupled with Giancono’s discovery yesterday, I was confident of a find as I set off for a 3km walk through the desert, determined to be the one that would radio back to base with good news for Anderson. The vastness of the Nullarbor quickly dashed most of my expectations, but highlighted the effectiveness of the drone method, and as I optically scanned the planet’s surface I reflected again on how incredible (and preferable) it is to perform a targeted search this way. With my hopes up as I reached each of the stage 4 locations, it is difficult to describe the disappointment of discovering, yet again, more poo. We are running out of time, as our stocks of hummus and beer are dangerously low, meaning we may not be able to complete our mission. Anderson reminded us of the trip’s true purpose: to transfer some of his knowledge before he leaves for a new commission at NASA.

Although he meant to instill in us a sense of success and achievement, Giancono and I would still very much like to find the meteorite, so we continued what we could of the search while assessing our options for a safe return to civilisation. Fire may close our path to the west, and an approaching thunderstorm from the south provided an impressive light show over rations, with more than a strike each second.

We watched as the stars overhead became more obscured, and as the wind picked up we retreated to Rhonda to ride out the storm. With the three of us in the small cabin for an unknown duration, we regretted that our last meal was lentil and bean chilli. Walker out.

day 7&8 - drive back dodging bushfires

Captain’s log, star-date 20231209. The only casualty from the storm was my flight suit, used to strengthen the canopy and protect Rhonda’s porthole during the worst of the weather. Giancono and I completed our last walks to meteorite candidates/poo, and then re-packed our craft to begin the voyage home. We followed the supply train line for 1.69817e-11 parsecs/5.53868e-11 light years/530km, to a remote outpost that also values precious rocks (Kalgoorlie).

Events of note: a cavity in the road pushed Rhonda into an unscheduled flight and caused a temporary loss of some cargo. Anderson found a tektite as he opened the hatch.

Giancono poured most of the feta oil on the ground during a rest stop, which caused Anderson some distress. Over a carb-heavy meal that we didn’t need to prepare or clean up ourselves (luxury!), we reflected on the mission parameters, and shared our most memorable moments. Having not seen evidence of more spiders since the man-eater on day 2, I found it remarkable that I saw the only arachnid in the Nullarbor. On a completely unrelated note, Anderson received a large two-pronged bite on his waist (which he only discovered after his first shower in 8 days). We are now only a few hours from base, and I look forward to the indifference of my feline beasts. This is my final entry for this mission - an experience I’ll never forget.

Walker out.

Bonus pictures